A tuberculosis vaccine candidate under development at Texas Biomed shows complete protection and superior immune response in nonhuman primates compared to the existing BCG vaccine.

SAN ANTONIO (March 4, 2025) – A live-attenuated tuberculosis (TB) vaccine candidate in development at Texas Biomedical Research Institute (Texas Biomed) elicits a much more balanced and effective immune response compared to the existing vaccine used across much of the world, according to preclinical research published in Nature Communications.

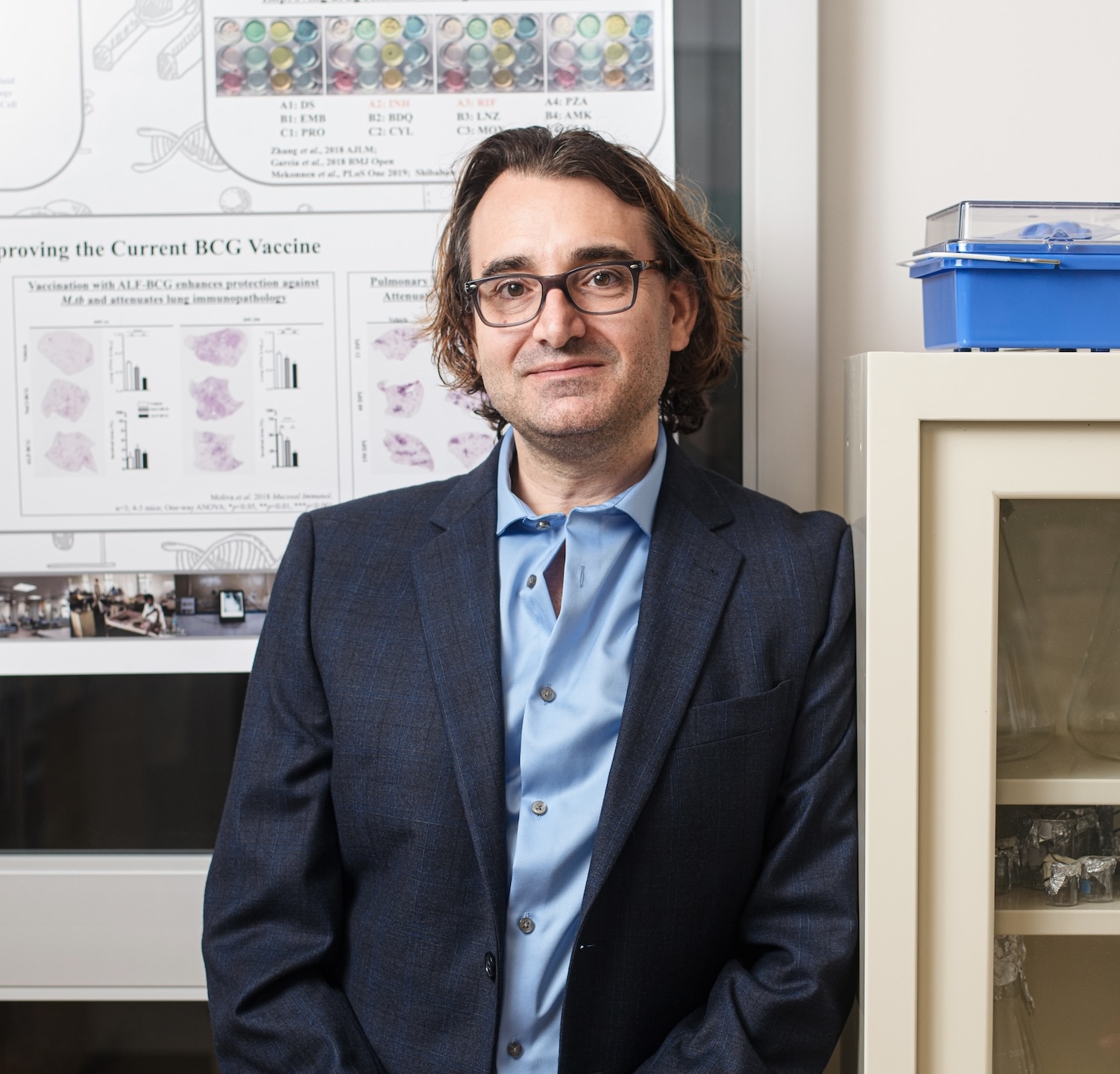

The vaccine candidate, being developed by Professor Deepak Kaushal, Ph.D., involves a weakened or “attenuated” strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the bacterium that causes TB.

Dr. Kaushal has been working to develop a better TB vaccine for more than 15 years. In 2015, he showed that this vaccine candidate was 100% protective against a lethal dose of Mtb in rhesus macaques.

“Immunology has changed a lot in 10 years and now we can do much more in-depth experiments that show not just that this vaccine works, but why it is working,” Dr. Kaushal said. “That is what I am most excited about with this paper – showing the mechanisms that provide this elite protection, which can inform not only our work but any next-generation TB vaccine.”

New TB vaccines are needed

TB is the leading killer worldwide by a single infectious agent, claiming more than 1.25 million lives in 2023 and infecting more than 10.6 million, according to the World Health Organization. The only licensed vaccine on the market – the Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine – was invented more than 100 years ago and its effectiveness is limited in adults.

Dr. Kaushal’s vaccine candidate is called delta sigmaH – he has modified the bacterium by deleting the gene needed to make a protein called sigmaH (sigH). Without sigH, the bacterium is unable to fight off oxidative stress properly and cannot survive in the lungs.

In the current study, Dr. Kaushal and his team at Texas Biomed retested the delta sigH vaccine in a different species of nonhuman primate, cynomolgus macaques. Nonhuman primates are the gold standard to understand how a complete system will respond to a treatment or vaccine, before moving to clinical trials in humans.

“By analyzing this in a different species, this shows it is not just a one-off and gives us more confidence the vaccine is likely to work in humans,” Dr. Kaushal said.

Different immune responses

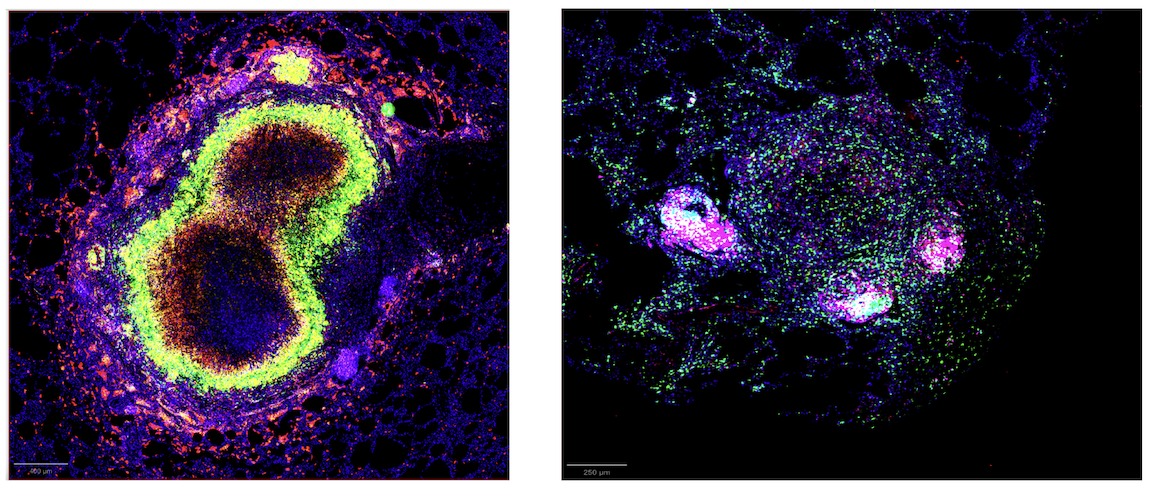

The team used single-cell RNA sequencing and advanced imaging techniques to compare the immune response between animals vaccinated with BCG and animals vaccinated with the delta sigH vaccine. While both groups were able to control TB, there were dramatic differences in the immune response.

The delta sigH vaccine resulted in a much higher recruitment of critical B and T immune cells to the airways. Importantly, this did not result in excessive, harmful inflammation. Rather, a cascade of responses led to a more balanced and effective elimination of the bacteria.

Notably, the delta sigH group had much lower levels of IDO, a protein known to cause more inflammation and make it difficult for the immune system to combat TB, compared to the BCG group. There was also a significant difference between the type of interferon triggered. Interferons are proteins that help fight infection. Typically, BCG induces a strong Type I interferon response, which in turns leads to higher levels of IDO. With delta sigH vaccination, interferon gamma, a cytokine that belongs to the other main class of Type II interferons, appears to take a leading role and modulate the immune response.

“With delta sigH, it looks like we are getting all of the good aspects of interferon signaling and none of the bad,” Dr. Kaushal said.

A few more steps of the pathway still must be pieced together. Other key remaining questions are: How long does protection last? Is the vaccine as effective delivered via a typical shot versus directly to the lungs? Dr. Kaushal and his team are also working to develop and test versions of the delta sigH vaccine with more than one gene knocked out so that they can be safely tested in humans.

“The next round of studies are underway,” Dr. Kaushal said. “While we are still years away from seeing this vaccine in the clinic, these latest results are giving us more insight to fight this insidious disease.”

Paper:

Singh, D.K., Ahmed, M., Akter, S. et al. Prevention of tuberculosis in cynomolgus macaques by an attenuated Mycobacterium tuberculosis vaccine candidate. Nat Commun 16, 1957 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57090-4

Funding:

This research was supported by NIH grants AI185028, AI134240, AI138587, AI111914, and institutional NIH grants OD011133, OD010442, OD032443, OD028732, AI161943, AI168439, OD028653 and OD028732.